This is the third installment of a three-part story. In part one, a bankrupt music promoter and his detoxing son attempt to stage a Nas concert in Angola — and become trapped when the show implodes. In part two, with their passports confiscated and heroin withdrawal setting in, they ask a team of mercenaries for help. Skip to: Part 1 | Part 2

Chapter 11

Patrick Allocco Jr. never thought he’d be stone-cold sober again, and he certainly never thought it would be poolside at a hotel in Luanda, Angola. He’d been trapped there after a debacle involving a thwarted New Year’s Eve concert involving Nas and an intimidating promoter called Riquinho, who used his clout with local authorities to prevent Patrick Jr. and his father, Patrick Sr., from leaving the country. They’d had their passports confiscated twice, been intercepted by armed men en route to the U.S. Embassy, been interrogated by police, and had a near-miss rescue with some South African security operatives and a helicopter.

Patrick Jr. sweated through the uncertain days — and a vicious withdrawal from heroin — in their hotel room. They’d just been told they were “too exposed” to Riquinho’s surveillance where they were, so Alloccos moved hotels. The Epic Sana was quite an upgrade: It was the toniest affair in town, close to the waterfront, with a grand atrium, silver tea service, a nightclub, and rooftop dining with a commanding view — although few of those amenities were open. The Sana was still partly under construction, taking guests while gearing up for its grand opening. And yet it cost some $475 per night for a room with only a single queen-size bed.

“Been a long time since we shared a mattress!” said Patrick Sr., trying the lighthearted approach. Patrick Jr. was not amused.

In their new digs, father and son were a bit of an odd couple. Patrick Sr.’s clothes were in the dresser neatly folded; Patrick Jr.’s were lying in a heap. They bickered. Patrick Sr. couldn’t stand how much his son was smoking. The kid was like a chimney. Patrick Jr. discovered his father was using his shaving cream and always leaving foam on the nozzle.

“Get your own shaving cream!” Patrick Jr. yelled. Patrick Sr. couldn’t understand why it mattered. “You were homeless, and you care about your shaving cream?” he said, a bit of a low blow. In truth, Patrick Jr. didn’t shave all that much. But the one thing Patrick Jr. had learned in military school was to keep the shaving-cream nozzle clean, and for him, it was a matter of principle. “Just rinse off the top and put the cap back on,” he said.

As the days ran together, the Alloccos settled into a strange routine. They slept at odd hours because of the time difference with the U.S. They had breakfast at the $75 buffet, often at 3 p.m. They watched TV, mostly in Portuguese. Patrick Jr. built a line of pillows down the center of the shared bed, so there’d be no accidental midnight spooning. But no number of pillows could drown out his father’s snoring. “You sound like a dying bear,” Patrick Jr. said.

To make space, Patrick Sr. moved his makeshift office to the hotel restaurant or sometimes the patio, where he stayed in contact with the embassy, his U.S. political connections, and other supporters. He took to social media, asking for help on a “Free the Alloccos” Facebook page. He circulated a petition demanding the State Department assist in their release. He had further success with the media, calling in live to the evening news on New Jersey 12 TV and radio stations like WABC and WKDU in Philadelphia. The Newark Star-Ledger did a feature. He even went on Geraldo Rivera’s show. But it was frustrating, having the same conversations on repeat, telling the tale over and over, a story with no ending.

While his father made calls and media appearances, Patrick Jr. wandered the Epic Sana, wondering why the conference rooms were always empty. For a business hotel, there never seemed to be anyone doing any business. It was also puzzling that Christmas music still drifted from hidden speakers throughout the facility. It was mid-January, deep in the tropics, but at all hours of the day you could hear an off-brand cover of Gene Autry’s ditty about that magic moment when Frosty the Snowman was brought to life by his magic hat. Patrick Jr. amused himself with the thought that maybe he had actually died on the streets of Newark and this was all some kind of purgatory.

In the afternoon, Patrick Jr. could often be found in the infinity pool, which was nice even though there was a small construction site with a sign advertising a new pool bar that never appeared to near completion. Evenings were spent in the hotel’s lounge, bullshitting with a bartender named Joel while drinking club soda. Patrick Jr. had thinned out by 20 pounds, and his clothes barely fit him. He looked fairly shabby compared to the business-traveler crowd, but as usual, he had an easy time talking to strangers: Israelis, Canadians, a Swede, and a man of indeterminate origin who was bald and had devil-themed neck tattoos and turned out to be a tech consultant. One night when Patrick Jr. stepped out to smoke, he met an Iraqi who was in Angola for an oil contract. “What are you doing here?” the man asked. Patrick Jr. told him. The Iraqi expressed his sympathy but was unsurprised. “It’s just how Angola works,” he said. “This isn’t America. Best of luck!”

At night, Patrick Jr. often stayed up late talking to Rachel on a messaging app called Tango, trying to convince her to get back together with him. They’d been in contact since before he left for Angola. She’d been keeping him at an emotional distance but also held out hope that the trip might be a step toward turning things around. Little did she know that he would wind up trapped halfway around the world. When Rachel told her co-workers at the Morristown Sushi Lounge what had happened to him, they didn’t believe it at first. Then it appeared on the local news. “Isn’t that your boyfriend?” a co-worker asked. “Ex-boyfriend,” Rachel said, staring at the television mounted above the bar.

It was the same bar where Rachel and Patrick Jr. had met the previous spring. They’d flirted a bunch, until one day they got into an enormous argument that spilled out from the kitchen into full view of the packed restaurant. Patrick Jr. was fired the next day. A few months later, he texted Rachel out of the blue. It was the middle of a heat wave and his apartment had a pool, so he invited her over. He was clean, he said. After another tour in rehab — he’d nodded out while driving and sideswiped a fire truck — Patrick Jr. had clocked a good solid month on the wagon.

Against her better judgment, Rachel went — and had an instant connection. They wound up spending the summer together, getting close quickly, even though she knew his history; her own brother was an addict. Patrick Jr. didn’t quite understand why Rachel stayed with him, especially as drugs crept back into his life. Rachel was different from most girls he’d dated. She had gone to college. She had her life together. And she hoped he could do the same. “You can do better,” she’d tell him.

Patrick Jr. heard the message, but his addiction was stronger. His biggest fear had always been falling into the same trap as his mother, and yet there he was. At times he had been shooting close to 50 bags a day.

But after several weeks in Angola, Patrick Jr. was clean again, and Rachel rediscovered the sweet guy she’d originally fallen for. For hours at a time, Patrick Jr. entertained her with dispatches from his detainment, the people he met, and complaints about his father. “He won’t stop talking about social media,” he told her. “It’s driving me crazy.”

But Rachel also detected warmth in Patrick Jr.’s voice when he talked about his father. After all, the two of them were spending more time together than they had in years. “Yeah,” Patrick Jr. said. “It seems like we might actually be getting along.”

Rachel became Patrick Jr.’s emotional lifeline. He went through the long days looking forward to their late nights on Tango. And during those marathon calls, with the Atlantic Ocean and six time zones between them, Rachel found herself drawn to Patrick Jr. again.

“When will you get home?” Rachel asked.

Patrick Jr. had no idea. He said it felt like they were in some kind of strange sequel to Groundhog Day. “We’re just waiting for something to happen,” he said.

Chapter 12

It was a strange relief to be formally charged. One morning, several inspectors had arrived at the hotel and told the Alloccos to report to a DNIC building nearby. They entered a wood-paneled conference room and sat at a horseshoe table. At the other end was Riquinho, glaring, with an attorney. Finally, they were at a hearing. Patrick Sr. had only recently found lawyers who would take their case, and he was meeting them in person for the first time. They’d been in Angola for three weeks.

The Alloccos’ attorneys explained that the presiding official was called a public prosecutor, although the role was equivalent to a judge. He entered, draped in a black robe. “We want to work something out where everybody’s happy,” the public prosecutor said in perfect English. “Sons of bitches,” Riquinho muttered.

The immigration charges were dropped, which was a nice break, but there was still the dispute over the missing funds. Riquinho accused the Alloccos of fleeing justice. The Alloccos said they’d only done what the U.S. Embassy had suggested. Riquinho said they were crooks, intent on defrauding him from the beginning. The Alloccos said Riquinho had scared off Nas with his bad reputation and dodgy paperwork. The public prosecutor took what the Alloccos saw as a reasonable view, deciding that once the $300,000 was in Riquinho’s hands, they’d negotiate a final settlement out of court for the rest, paid in installments once they got back to the U.S.

The session adjourned, and it seemed like a breakthrough. The $300,000 was returned to Riquinho. But a few days later, when he sat down to negotiate the remainder with the Alloccos’ attorneys, he ignored the judgment and demanded a lump sum.

This wasn’t possible. The weeks in Angola were digging Patrick Sr. into a deeper hole; every day saw him another $1,000 short. Of the remaining $100,000, he only had $25,000 left. He wanted to explain this to Riquinho, but their every communication was fraught. In another negotiation, Riquinho asked Patrick Sr. to compensate for the losses in ticket sales. To return to the judgment, they’d have to get back in front of the public prosecutor. But no return date had been set and it was unclear how to get a second appearance. Patrick Sr. posted another appeal online to the U.S. government to “intercede [and] have the travel restrictions released.”

At the embassy, State Department officials would have loved to send the Alloccos home, but they too were at the mercy of the local government. Ambassador McMullen’s working group met twice a day to strategize; they would call the foreign ministry or send the consular chief to various government offices without success. Riquinho’s influence with the government was too strong. “The bigger problem,” McMullen said later, “was the nature of the government itself.”

José Eduardo dos Santos had been in power for 30 years, and he was both the president and the head of the ruling party; all of the country’s politics and business went through him. “It’s a patronage system,” McMullen said. “All government offices are rewards for loyal party members.” As a result, everyone in a government position was so worried about making a decision that would upset dos Santos that they made no decisions at all.

McMullen was on his eighth foreign-service assignment, and he had never experienced anything quite like Angola. In other countries, the U.S. Embassy staff have reliable counterparts for different issues — trade, economics, etc. Not here. There simply was no professional bureaucracy, and it is through bureaucracy that governments resolve conflicts. The Alloccos’ case was an inversion of a Kafka story: Instead of being trapped in a vast, vindictive bureaucracy, they were floating in a bureaucratic void. When the ambassador would try to reach the foreign minister or the attorney general, they often wouldn’t answer the phone. “It was an extremely opaque system,” McMullen said. Sometimes it wasn’t even clear who to call at all.

Chapter 13

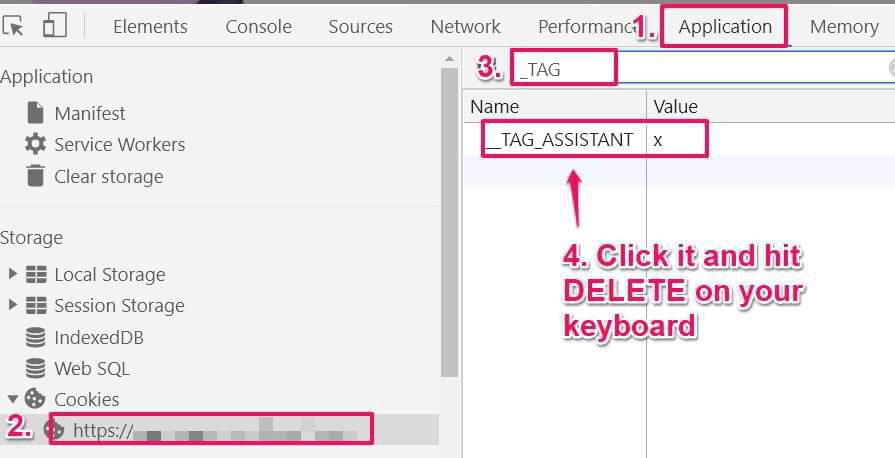

Illustration: Zohar Lazar

The days dragged on. Mornings became afternoons became nights became mornings. The sun turned the port deep blue. The city wavered in the heat. The moon shone on the pool. There was still no news from the embassy or any word about a second court date. Patrick Sr. spent so much time continuing his media blitz and trying to gin up political pressure that he discovered one afternoon that his phone bill was nearly $18,000. Guess I should have gotten that international plan, he thought. Panicked about losing his cellular lifeline, Patrick Sr. called AT&T customer service (“You’re not gonna believe this, but …”) and wrote a letter to the chairman to convince him to waive the charges.

Patrick Jr. spent more time in the bar with his elbows propped on the granite, chatting up Joel and his colleague Lourdes. The barkeeps cleaned the glasses, listened to their new regular’s troubles. When the bartenders would ask when he was going home, he’d answer: “Never — I live here now!” If travelers asked where the kid who always sat at the bar came from, he’d say, “Angola!” It always got a laugh. But, in fact, Patrick Jr. had been here longer than anywhere else of late. For months in New Jersey, he’d been living on the streets, in shelters, and in tents. Luanda was just another unknown place he’d landed, and it was better than many of the others.

There was an irony to the Alloccos’ new routine, taking meals together and roaming the Epic Sana, waiting for that promised pool bar to open. Part of Patrick Sr.’s pitch back in December was that their Angolan excursion would be a kind of family vacation, a poolside jaunt in the tropics. Here they were, by complete accident, on that fictional vacation. Even if it was involuntary and indefinite.

And yet father and son were surprised to be enjoying their time together. It was a little tight sleeping in the same bed, and the glass-walled shower that faced into the room wasn’t ideal, but they made the best of it. Their fear slid into boredom, and they learned to celebrate the small things. They ordered room service and watched a lot of TV. At times, it was like an endless sleepover, being up at weird hours, eating ice cream, revisiting John Cusack movies, and trying to decipher Disney cartoons dubbed into Portuguese.

Their favorite program was a Canadian reality show called Mantracker, where two contestants are dropped in a remote wilderness and must survive while being pursued by an expert tracker. There was something comforting about watching other duos trapped in an unfamiliar environment, fording frigid lakes and avoiding wolverines. Although it was disconcerting when the tracker would show up, often mounted, and lasso his prey into submission.

The Alloccos also started getting out of the hotel, exploring the neighborhood. Kids on the street began to recognize them. They got high fives and fist bumps while walking to the supermercado and found a stall that sold rotisserie chicken. Patrick Jr. made friends with some of the local panhandlers, and he always gave them money.

One day, the Alloccos walked to the Church of Our Lady of Remedies, a 17th-century Catholic cathedral. Patrick Jr. was crapped on by a bird, which he told his father he took as a sign.

“What kind of sign?”

“Good question.”

The church was a colonial relic but beautiful, with a rose window and delicately painted nave. They stood in silence at the gold altar. Patrick Sr. thought: Junior and I haven’t been to church together in 15 years. He lit a votive and promised the heavenly Father that if he ever made it home, he’d get better about going to Mass. Okay, Lady of Remedies, he thought. Let’s see what you got.

They had not prayed for pizza, and yet when they happened across Ciao, a genuine pizzeria not far from their hotel, it felt like divine intervention. An Italian expat named Elio, they were delighted to learn, had dedicated himself to serving his authentic home cuisine and imported enough fresh ingredients to present a variety of pies. The food was well priced and spot on: decent pasta, great pizza, just like half the joints back home. Patrick Jr. had started putting on weight again, and it felt great digging into a bowl of carbonara. Patrick Sr. favored the salami picante 12 inch. Ciao became an oasis. They felt both at home and homesick, thinking of New Jersey, the grass in the backyard, the skyline across the river, the traffic, the toll roads — even the freaking turnpike was a source of nostalgia. “I think this is among the best pizza I’ve ever had,” Patrick Sr. said.

The Alloccos roamed further. They walked to the Marginal and strolled beneath the palms along the waterfront. Patrick Jr. said it reminded him of the Pirates of the Caribbean ride at Disney World, where they’d first gone when he was 7 years old. “I can still smell the smoke from the cannons,” he said. Visiting Orlando became an annual ritual, and Patrick Jr. looked forward to those trips every year — until the summer before eighth grade, when things started to unravel. Disney World was the last place they’d been on an actual vacation together, before now.

Chapter 14

The Martin Beck Theater was sold out for the Broadway revival of Annie. It was 1997, and Patrick Sr. had gotten orchestra seats for his 8-year-old son. After the curtain call came a surprise announcement: Annie’s canine sidekick, played by a Siberian husky named Nevada, was up for adoption by raffle. “I want her!” Patrick Jr. told his father, mesmerized by the dog’s wolfish coloring and blue eyes. A week later, the phone rang: Nevada was theirs. Patrick Jr. did an actual jump for joy.

A few years later, Patrick Sr. was married to Abby. Life never was a perfect suburban idyll, with the frequent turbulence around Patrick Jr.’s mother; but when Abby would watch father, son, and Nevada sitting fireside during the holidays, listening to Patrick Sr.’s favorite Kenny G Christmas compilation, it almost felt like a normal family.

There was a time when the vitriol of Patrick Sr.’s divorce from Joellen faded, and incredibly, they became friends. For a while, she seemed in control. She came to school plays, joined for Patrick Jr.’s first communion, got him a bunny for Easter. But when her addiction took over, she kept finding herself in trouble with the law: drug charges, robbing a convenience store. Once, she was picked up by state troopers while trying to hitchhike by flagging down cars with her bra, and when they took her back to the station, she stole a police tow vehicle and led several squad cars on a chase up I-95.

Patrick Sr. knew that growing up with a troubled mother wasn’t easy. He tried to shield his son as best he could. One year, Joellen was arrested just before the holidays and was released from Rikers Island at midnight on Christmas Eve. Patrick Jr. had no idea his father spent the day racing around to find the gift his mother and her boyfriend had promised him — a boa constrictor — so she could give it to him the next morning as her own. (Joellen says the snake thing happened at a different time of year.) But by then she was already high.

Patrick Jr. was traumatized. When he’d have a nice normal dinner at his friends’ houses, he wondered why his family was different. Even at his father’s home, Patrick Jr. felt neglected at times. Patrick Sr.’s work often made him absent. When he wasn’t traveling, he was always on the phone, preparing for a show. Once, Patrick Jr. made a connection with one of Joellen’s boyfriends, an ironworker who gave him a bolt from the wreckage of the World Trade Center, where he was on the cleanup crew. Patrick Jr. could still smell the fire on it. When he showed the bolt to his father and said he wanted to be like the man who’d given it to him, Patrick Sr. said, “No son of mine will be an ironworker,” and took it away.

Patrick Sr. admits naïveté about the reality of his ex-wife’s addiction — and his son’s. He had no idea that the first time Patrick Jr. got drunk was at his wedding to Abby. He was 10. By eighth grade, he was drinking at school and barely graduated from junior high. When Patrick Sr. found out, he went from denial to counterproductive notions about “problem solving” the addiction. He tried hippie techniques and tough love. But their talks would escalate to catastrophic blowouts.

Patrick Jr.’s time with his mother made things worse. As a teenager, he says, he’d smoke weed with Joellen and share pharmaceutical recommendations. She encouraged his double-zero ear spacers and took him to get his eyebrow pierced. She told him she’d never judge him, and she didn’t. But there arose a perverse camaraderie, being in the trenches of drug life together. When Patrick Jr. turned 18, he got her name tattooed across his chest. She introduced him to her dealer, brought him smokes in rehab, asked him to pick her up when she got out of jail. Eventually, his mother disappeared more often, and his father got sole custody. Once, the U.S. Marshals showed up at Patrick Sr.’s house, looking for her. “I haven’t seen her in months,” Patrick Jr. told them.

At 17, he dropped out of high school. There was a heartbreaking illogic to Patrick Jr.’s first experiment with heroin: If the high is so good that my mother abandoned me for it, he thought, maybe I should try it.

On the night of the overdose, in the fall of 2011, Patrick Jr. showed up on his father’s doorstep, certain he would be turned away. He still isn’t sure why his father let him in. Patrick Jr. said hello to Nevada, who was by now a geriatric 13, and disappeared into the guest room downstairs. He sucked the dope into the syringe and heard the pop. He thumbed his skin for a vein. The plunger sank. His eyelids fluttered. He swallowed some Xanax and took off all his clothes. The warmth spread in a wave. It was the last thing he remembered.

A few minutes later, Patrick Sr. was headed to bed and heard a strange sound coming from the guest room, like a large animal wheezing. He tried the door, but it wouldn’t open. The loud, uneven rasping was just on the other side. Panicked, he forced the door and found his son lying on the ground with a vacuum hose around his neck.

Patrick Sr. had been a volunteer paramedic for years and had brought people back from overdoses with Narcan. But no amount of training can prepare you for finding your own son on the floor, unresponsive, face blue. For a second, Patrick Sr. could barely remember how to dial 911. His hands were trembling as he uncoiled the hose, rolled Patrick Jr. over, and managed to get him breathing by the time the ambulance arrived. He watched the paramedics put Patrick Jr. on a stretcher, checking for a pulse as they rolled him out the door.

Patrick Jr. woke up the next morning in the hospital, chained to the gurney. He was almost annoyed to be alive. Every day was a ritual of misery. His compulsion felt like a curse. He was estranged from everyone he loved. Nurses removed his restraints just long enough for Patrick Jr. to sneak out and walk back to his father’s house, where he showed up on the doorstep, his ass hanging out of his hospital gown. He was allowed in only to retrieve some clothes. On the guest-room bed, there was still debris from the effort to revive him. Patrick Jr. got his things and shuffled off into the night. Maybe his dealer would be down at the Chicken Shack. Maybe it would all be over soon.

It was the week before Thanksgiving, and this was not how Patrick Sr. had imagined the holidays. What he wanted was his family around a festive table, cranberry sauce shimmering on a saucer, getting ready to pull the Christmas ornaments out of the closet. Instead, his future was in jeopardy, his son a ghost. Throughout Patrick Jr.’s addiction, he’d missed birthdays, Easters, the Fourth of July, but he’d always managed to make it for Christmas. This year, Patrick Sr. didn’t even bother to get a tree.

Chapter 15

A giant inflatable Santa Claus presided over the festive scene in the center of Luanda’s Belas shopping mall. The Alloccos were on an outing led by Lourdes the bartender from the Epic Sana, who’d become their informal guide to new parts of the city. It was a nice afternoon, and for a few hours it felt as natural as any day back in New Jersey: going to the food court, window shopping, checking out what movies were playing. Mission Impossible: Ghost Protocol was starting soon and, miracle of miracles, it was not dubbed. They ate Reese’s Pieces and watched Tom Cruise execute dramatic escapes. After a couple of hours, they emerged from the dark theater, blinked in the light, and resolved back into the reality that they were still in a mall in Luanda, with Andy Williams singing “It’s the Most Wonderful Time of the Year” over the loudspeakers. It was almost February.

Lourdes was also the Alloccos’ social director, introducing them around, inviting people to the Epic Sana to meet them. As usual, Patrick Jr. had no trouble making friends, and through Lourdes he gained entrée into a circle of young middle-class Angolans. There was Osvaldo, who had a substantial gut and always wore basketball jerseys so tight they looked like a new line of NBA-sanctioned maternity dresses. Erickson was a finance student who wore cornrows and drove the group around in a white minivan. Joseph was always in designer ensembles that made his horn-rimmed glasses even more chic.

Osvaldo’s English was good and he knew quite a bit about the U.S. He started coming to the hotel every day and would talk with the Alloccos for hours. At first they thought he might be a plant from Riquinho, but Patrick Sr. liked him and decided he was legit. Osvaldo translated paperwork and answered questions about the courts and police.

The Alloccos’ story was often in the local papers. “It says you are devils and American thieves,” Osvaldo read aloud, laughing. “You’re famous!” It turned out Riquinho had been mounting his own media drive in Angola. Back in the U.S., Patrick Sr.’s public pressure campaign was catching on. His “Free the Alloccos” Facebook page helped assemble a small army of online advocates. An AP reporter covering the State Department started asking Secretary of State Hillary Clinton’s spokeswoman about the Alloccos at briefings. From Luanda, Patrick Sr. watched every session online, hoping they would build more pressure to resolve their case.

Meanwhile, Patrick Jr. was enjoying the city. His new pals took him to clubs and to Ilha de Cabo, the South Beach of Luanda, where they flirted with girls dancing to Shakira. Patrick Jr. said they were his “Angolan family,” and he was half-serious: Back in New Jersey, he’d had no social structure for some time. When he was homeless, Patrick Jr. mostly found himself alone or among strangers on the streets, or in rehab, or shooting up. In Luanda, he had his father, his pizza place, his local market, and his crew. Strange to say, but at the moment the best version of his life was in Luanda.

He connected in particular to Erickson, who liked that Patrick Jr. was easygoing and wanted to learn more about Angola. He was excited to show Patrick Jr. around to his other friends. “Where did you find this guy?” they asked.

Erickson also brought Patrick Jr. to meet his family, who lived in a nice house not far from the hotel. Inside, Erickson’s brothers and stepmother were getting ready for dinner. They had a chow dog, blue tongue waggling. When Erickson’s father came in, he joked, “Who is this white guy in my house?” As they sat down to dinner, ate funge, and watched soccer, Patrick Jr. felt nearly at home. Erickson’s father was a journalist, well traveled, and he asked Patrick Jr. a lot of questions.

At one point, Erickson took out an iPad. Patrick Jr. had never seen one. This stunned the entire household: “Impossible!” Erickson said. Patrick Jr. wanted to explain that back home, he was a junkie, hadn’t had spare money in years, couldn’t imagine getting his hands on a luxury item, other than to maybe sell it for cash. Instead, he played along with the whole family’s disbelief. “Here you are, from America, and you have to come all the way to Angola to see an iPad?”

Erickson was proud to show Patrick Jr. his country and culture. People have a vision of Africa as the end of the world, he said, but the reality is the opposite. Erickson was ordinarily guarded around white people; he’d studied for two years in Portugal and had been thrown by the racism he’d encountered. He’d felt isolated and couldn’t study, and there were unpleasant incidents. But Patrick Jr. was different —the first white person Erickson could call a friend.

One night, Patrick Jr. was hanging out at a soccer pitch near Erickson’s home. The temperature had dipped just enough to make for a pleasant tropical evening. There were musicians nearby and smoky food carts grilling lamb over charcoal. People were drinking and eating and there was a group of boys doing capoeira. It was an enchanting sight. Many of the people in the park had likely endured hardship, Patrick Jr. reflected. And yet here they were, enjoying life, something he had forgotten how to do a long time ago. He had no idea when he was going home, and in the moment, it didn’t matter. Sometimes life surprises you with unlikely moments of joy. “I couldn’t turn away,” he said, telling Rachel about it later. “It was just so beautiful.”

Chapter 16

Scott Reed was having a steak and a glass of wine at Morton’s, a Washington steakhouse for the political elite, when he saw Senator Menendez and his chief of staff, Danny O’Brien, at a table nearby. “Pardon the interruption,” he said, approaching them, “but it seemed like too good an opportunity to pass up.”

Was the senator aware that his two fellow New Jerseyans remained stuck in Angola? “Yes, we are engaged with it,” Menendez said. These were extraordinary circumstances, he said, but they would redouble their efforts. “We are dealing with State every day,” O’Brien added, “and talking directly with the embassy.” But the news, he admitted, was slim.

After running into Reed, Menendez decided to call Ambassador McMullen directly. Rodney Frelinghuysen, the congressman from Patrick Sr.’s district, was an old friend and had also reached McMullen several times. McMullen was candid with both officials about the stalemate. “When I briefed them,” he later said, “I didn’t sugarcoat anything.”

McMullen had realized that dos Santos was paying attention to the case personally. “A decision like this — and really all government decisions in Angola — would ladder up to the president,” he said. This kind of “visibility” complicated things because the regime’s patronage-based apparatus made it difficult to access the president’s office. He said that they’d simply reached the extent of their diplomatic clout.

“We need to escalate this somehow,” McMullen told O’Brien. They decided that Menendez, with his perch on the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, would draft an official letter to be delivered to dos Santos. Sometimes, ink on the right letterhead can get things moving. O’Brien got the go-ahead from the State Department and drafted a document. Menendez offered his signature and said, “Let’s hope this works.”

Chapter 17

The trouble with being pals with the bartender is that you wind up spending a lot of time at the bar. It may have been just a matter of time before Patrick Jr. told Joel to pour him a Cuca, the national beer of Angola. He’d been sober for a while, longer than any recent stretch. But he’d been trapped in this outlandish situation for so long he figured a drink was harmless.

The glass was cold. No one has ever said Cuca is a great beer, but it looked like magic, all gold with a white head. The lager hit his throat, and the lights went dim for a nice long moment. From the first sip to an empty glass was no more than a minute. “Shot of Jameson,” Patrick Jr. said. Joel had no Jameson and no shot glasses, so instead he filled a rocks glass to the brim with Bushmills.

Booze hadn’t been Patrick Jr.’s inebriation of choice in a long time, but it came back easy. Joel kept pouring, and Patrick Jr. kept drinking until he slid off the stool. Same thing the next day. And the day after. Patrick would show up in the afternoon, still groggy, and Joel would already be pouring him a pint of Cuca and some Bushmills. Joel started calling Patrick Jr.’s tall servings of beer and whiskey “mother’s milk.”

The outings with his Angolan friends stretched into late nights at Luanda’s clubs. Osvaldo and his crew hit the small hours pretty hard, and when in party mode Patrick Jr. had never been one to sit on the sidelines. They’d keep the shots coming and dance for hours, even Patrick Jr., who was not exactly light on his feet. Erickson couldn’t believe how much energy Patrick Jr. had. After closing time, they’d eat street food or Patrick Jr. would wander back to his hotel and sit down to breakfast with his father, who was just getting up.

When Patrick Sr. found out his son was drinking, he didn’t like it but mostly kept it to himself. “I know this whole thing is a shitty situation,” he said. Patrick Jr.’s new schedule felt like trouble brewing, but at least they were having breakfast together every day. That hadn’t happened since Patrick Jr. was a boy.

The Alloccos had been told to be careful, and Patrick Jr. was aware that it was a risk being out, but he was long past subtle consideration. And he was never great at following rules in the first place. That’s how he wound up at Club Mega Bingo that unfortunate night, when things went sideways and he had to flee across rooftops and eventually seek refuge at the U.S. Embassy.

Club Mega Bingo, as David Josar put it, “was a rough place for rough people, the one place you don’t want to go.” The embassy’s own staff were prohibited from going to the club for that reason. So when Patrick Jr. showed up at the embassy gates in his underwear, it was not a surprise once he explained where he’d been.

The guards put Patrick Jr. in a small room in the embassy, gave him a pillow, and told him to sleep it off, like the town drunk spending a night in the tank. At 5 a.m., Josar was rousted from bed to attend to the situation. Patrick Sr. was summoned to the embassy as well. Josar reminded him that he’d recommended they keep a low profile. “You guys really know how to get into trouble,” he said. When they woke up Patrick Jr., he explained the shakedown by Danilo, the guy he’d never met before. He couldn’t tell what Osvaldo’s role was. Erickson, he knew, was an innocent bystander.

Osvaldo would later explain that the incident began with an innocent night out. But in the club, he said, people recognized Patrick Jr. from the local newspapers and whispered about him being involved with Riquinho — which gave Danilo the idea for an impromptu extortion. Osvaldo said he tried to intervene and defuse the situation, but couldn’t prevent the mêlée in the street that left Patrick Jr. scratched and bruised.

For Josar and the other embassy officials, the competing stories didn’t matter because Patrick Jr. shouldn’t have been there in the first place. Whatever happened, it would not help their cause. Patrick Jr. was lucky not to get a new criminal charge from the Angolan police. “Take him back to the hotel,” Josar told Patrick Sr. “And don’t do anything like this again.”

Oddly, Osvaldo kept showing up at the Epic Sana, even after all that. Patrick Jr. was annoyed and avoided him. What upset him most, though, was that he never again saw Erickson, his one real friend in Luanda, the first he’d made in some time.

Nightlife was over, but Patrick Jr. kept drinking. There was nowhere to go but the bar. When Joel closed up at night, he started leaving the rest of the Bushmills bottle for Patrick Jr. to finish. “More mother’s milk!” he’d say.

The tedium was rarely broken. One surprise, however, was the day the Alloccos realized the Super Bowl was on. And the Giants were playing. Their home team from the Meadowlands! The game started past midnight in Angola, and the Alloccos were the only interested spectators in the bar. Here was a nice time, Patrick Sr. thought: father and son on Super Bowl Sunday.

It was a good game, a nail-biter — Giants leading early, then Patriots ahead for two quarters, with the Giants dramatically charging in the last two minutes. By then it was nearly 3 a.m. Patrick Sr. was riveted. But Patrick Jr. was half a dozen drinks deep and nursing dark thoughts. Watching the stadium crowd, Patrick Jr. was hit by homesickness. He looked around and realized where he was: stranded 10,000 miles from home, with a jungle, a desert, and an ocean in between and no way of getting home. Fucking bullshit. Absurd. The Giants traveled nearly the whole field to pull ahead with 57 seconds left: a triumphant win. But Patrick Jr. didn’t care; he was already en route to a meltdown. “Fuck this whole fucking thing,” he said.

Back in their hotel room, Patrick Jr. tore into his father. “I didn’t need to get dragged to Angola to die!” he said. “I was doing a perfectly fine job of killing myself in New Jersey!” He flipped a table. His father yelled at him to stop. It was a familiar maelstrom, like when Patrick Jr. was a teenager in his room. Patrick Jr. somehow did not shatter the glass bathroom wall when he hit it dead center with a chair. “Calm down!” his father said. “Calm down?” Patrick Jr. yelled on his way out the door. “You got us into this fucked-up situation!”

Patrick Jr. sat in the lobby, chain-smoking and stewing. Upstairs, his father was furious at the drunken assault but also stung by his son’s words. He had a point: This was all a cockamamie scheme. But he’d really believed this gig would turn everything around. And he had had no other options. It’s not like he wanted to be bankrupt. Nor was it entirely his fault. Patrick Sr. was in the hole partly because the promotion business was changing. The regional patchwork trade of promotion was being replaced by vertically integrated monoliths; AEG could book its own talent in 50 cities all through its own venue network. Patrick Sr. wasn’t inept; he was being eaten alive from the top. With few opportunities, small-time promoters were forced to take risks. These days, one of the only ways to score a big payday was some cockamamie scheme. So here they were.

The next morning, Patrick Jr. woke up with a hangover. He was in pain and embarrassed. His father was there, waiting. “I know this is stressful,” Patrick Sr. said. “But the drinking is a problem. You can’t act out or trash the room.” His tone was measured, calm. It was unlike the aftermath of previous substance-fueled skirmishes. Usually, being scolded by his father would have only escalated the hostility. But Patrick Jr was penitent. “You’re right,” he said. “I need to get myself together. I know you’re working to get us home.”

Almost without trying, their relationship changed. It had been many years since they’d had real conversations about anything, much less settled an argument with rapprochement. Now they talked all the time: over breakfast, at the pizzeria, and even at the bar, since Patrick Sr. had run out of Ambien and started heading there for a glass of white wine in the evenings.

One night, Patrick Jr. recalled some of his earliest memories, which were about one of his mother’s boyfriends. “I remember his motorcycle,” he said. “And how my mother sat me on the back to ride around.” Patrick Sr. was stunned at the danger — and the timeline: His son couldn’t have been more than 3 years old then. He realized there were a lot of things his son remembered that he never knew.

Patrick Jr. described the different men hanging around, the fighting, having his mouth washed out with soap, hiding under the covers in fear. He told him about the time his mother was high on heroin and he watched two cops drag her up the stairs. “Until she puked on their shoes,” he said. There was the time she wound up in the hospital and he was outside her room when the department of child services arrived to take him away. “Fuck you, bitch!” his mother yelled, busting into the waiting room, trailing a half-dozen security guards, who quickly took her down.

Patrick Sr. listened in shock. How had he never heard any of this before? These are things a parent is supposed to know. “I didn’t understand before,” Patrick Sr. said. “But now I do.”

The mutual resentments melted away. Patrick Sr.told his son how hard it was to watch him descend into addiction — but for perhaps the first time, he said it with care rather than judgment. Patrick Jr. knew the feeling. He’d watched his mother his whole life. Patrick Sr.recalled the unpronounceable agony of a father trying to breathe life into his dying son. The thought was like a lingering bruise. “You simply cannot imagine,” he said.

“I’m sorry,” Patrick Jr. said. At that moment, they each knew the other better than anyone in the world. Even Lourdes the bartender noticed, watching them bond a little more each day. “I see you two come together,” he said.

Patrick Jr. said that if he ever got home, he’d stay sober, get a job, perhaps join the ironworkers union like he’d always wanted. His father no longer seemed irked about his career ambition. Patrick Jr. said his perspective had changed in Angola. He had spent so much time pitying himself and nursing grievances when in fact he was fortunate. To Rachel, he proclaimed his renewed belief in the possibilities of life. He told her that he was looking forward to settling down with her, having a family. “Things will be different,” he said.

Patrick Jr. still doubted himself, burdened with regret. That’s the trick, of course, to overcoming the past and oneself. But thank God for Rachel: She believed in him — and called him on his bullshit too. She would help him stay humble, occupy the present, look to the future, and remember that what we’ve done is not everything we are.

Chapter 18

Patrick Sr. was nearly out of money but had to go shopping. He and Patrick Jr. were roaming Luanda, looking for outdoor supplies — mosquito nets, maybe sleeping bags — in case they had to sleep on the streets. Nearly two months of semi-captivity had drained their funds, and soon they’d have nowhere to go.

They’d been at the Epic Sana so long that the management offered them a few free days — “We’re on the rewards program!” Patrick Jr. joked — but Patrick Sr. knew that a few days wouldn’t make a difference. “Feeding ourselves will become a challenge tomorrow,” he wrote on social media. He listed some of their expenses, including their phone data overage, which he said had grown to $22,000. They collected a few donations from Patrick Sr.’s efforts online, but he calculated they’d run out altogether in 72 hours.

It was now mid-February, and the Alloccos were no closer to freedom. If anything, there were continuing setbacks. At Patrick Sr.’s last settlement conference, this time at police headquarters, Riquinho had changed the terms again and asked for an even larger sum, trying to make up for money lost on other failed concerts. A second court date had been scheduled — and then canceled with no explanation. Then the Alloccos’ Angolan attorneys had quit. They gave a reason, but Patrick Sr. wondered if they’d been pressured. He’d already paid them $20,000 of Riquinho’s money.

With no legal remedy, no representation, and no money, desperation set in. Patrick Jr. noticed that when his father watched Mantracker, he was paying much closer attention to the survival-skill demonstrations, like he was taking notes. Both the Alloccos’ thoughts had turned again to escape. After Patrick Jr. complained about their situation to Manuel, one of the waiters in the Epic Sana bar, he offered to drive them 700 miles to the Namibian border. They’d have to swim across the Okavango River and face its crocodiles, among the largest on Earth, but from there, Manuel said, they could get to South Africa. Patrick Jr. arranged a furtive meeting for Manuel to lay out the plan with his father. It would cost them $4,000 — everything they had left.

It seemed dubious, if not dangerous. What if it was a setup? Or another reckless folly? But there was little left to lose. The Alloccos went to the grocery store and stocked up on salami, cheese, and water for the overland journey. The next day, however, Manuel didn’t show up — for the drive or for work. The loss of yet another possibility for escape, even one so remote, hit the Alloccos hard.

But nothing affected Patrick Sr. as much as a call one night about Nevada. “She died this morning,” Abby said. His wife had been crying and was worried about breaking the news. “I heard her during the night,” she said, “and when I woke up she was dead.”

Patrick Sr. came completely undone. He woke up Patrick Jr. and could barely get the words out. Patrick Jr. had never seen his father that way, convulsive with tears, not even when his grandparents had died. Patrick Jr. thought that Nevada’s death seemed to represent something bigger to his father, a loss that stood for all the others. He understood the chaotic emotional spiral but felt the need to intervene. “You need to get it together,” he told his father, roles reversed. “We’ll all miss Nevada,” he said, “but we are still trapped and you need to focus on getting us home.”

The pep talk jolted Patrick Sr. back into focus. In his next online dispatch, he wrote that when their money ran out, they would leave the Epic Sana and camp outside the U.S. Embassy. That should get their attention, he thought. “Starting tomorrow …” Patrick Sr. posted. “We will begin taking matters and fate into our own hands.”

The knock was startling. Hotel staff usually called up to the room, so any time there was an unannounced visitor, the Alloccos worried it could be Riquinho, or his henchmen, or maybe someone else who would shake them down. Patrick Sr. was settling in for another evening of Mantracker. Patrick Jr. was in the bathroom, about to step into the shower. Patrick Sr. got up, looked through the peephole, and was shocked to see David Josar, other embassy officials, and security guards in plain clothes. “Get your things fast,” Josar said when Patrick Sr. opened the door. “You’re coming with us.”

They were given ten minutes. Still in a towel, Patrick Jr. got dressed and Patrick Sr. frantically packed. Embassy security took all of their electronics, swept their luggage for listening devices, and escorted the Alloccos separately downstairs, where the lobby was empty and the doors were blocked by embassy guards. The security staff told Patrick Sr. not to smile, talk, or draw attention to himself, but he still had to settle the bill with the hotel. The reception manager had tears in her eyes. “Looks like they’ve finally come for you,” she said. It was ironic, Patrick Jr. later joked, that earlier that day he had been genuinely excited about Epic Sana’s announcement that the pool bar would finally open.

The Alloccos couldn’t quite believe it. After months of stasis, here was the dramatic embassy rescue they’d been waiting for. Why now? Their case must have gone up to Secretary Clinton, they figured, or even President Obama, who surely authorized this mission. This is how it seemed to the Alloccos as they were led separately down the service elevator to the parking garage, a floor Patrick Jr. had never seen before, and whisked away in two armored SUVs.

The real reason was more mundane: Armed with the letter from Menendez, McMullen had escalated all the way up to dos Santos’ office. He spoke to the president’s personal adviser and explained that Menendez, as a committee head, held a lot of sway with the people and companies who invest in Angola. He pointed out that Angola was getting bad press as the situation dragged on. Angola needed foreign investment, and even though relations were strained, the U.S. was an important customer for oil. “At the end of the day,” McMullen later said, “the government realized the Alloccos weren’t worth the black eye. It was cost-benefit analysis. They got pragmatic.”

In the end, the Alloccos’ fate was determined not by mortal threat or conspiratorial forces but an advanced case of faulty organizational dynamics. Those months of waiting were just how much time it took the right offices in the giant machine of the State Department to rumble to life and persuasively communicate with the one office in the Angolan government that mattered.Once President dos Santos understood there was little to gain by letting Riquinho keep the Alloccos in the country, that was it. Like many things in life, the Alloccos’ misadventure in Angola boiled down to getting the right person to sign your paperwork.

Shortly after McMullen’s call, the embassy heard from the public prosecutor’s office. They wanted to see the Alloccos. This was why the embassy pulled them from the hotel. After six weeks of stonewalling, the Angolan court reconvened the following morning at nine on February 16. The public prosecutor quickly ruled that the Alloccos could leave Angola and pay back Riquinho in installments. Riquinho wasn’t happy, but his influence had been eclipsed. During the proceedings, the public prosecutor made sure to offer a fulsome declaration of “friendship between the governments of the United States and Angola.” The Alloccos were free to leave.

David Josar thought they were lucky it had only taken this long. “It was nice meeting you both,” he told them. “But I hope to never see you again!” The embassy staff gave the Alloccos a new set of passports and delivered them to the airport yet again. Incredibly, the immigration desk was manned by the very same officer they’d both met when entering the country. He took their new passports and examined them slowly.

Patrick Jr. thought about how he’d had to argue to get into the country from Lisbon on Christmas Eve. If only he’d known. The officials in Lisbon had said the documents Riquinho provided were not proper visas. Which they weren’t. Neither were those eventually supplied to Nas and his entourage. Which was why he never showed up. It wasn’t a scam or a grift or the cavalier whims of a rich rapper who saw an opportunity to defraud an Angolan promoter and leave two dudes from New Jersey stranded. Nas’s manager was experienced and recognized flawed documents. Those suspect documents set all the pieces in motion.

Standing in the airport now, the Alloccos watched their old friend at the immigration desk examine their passports and ask them to step aside. They were jittery, imagining that the diplomatic negotiations had somehow been undone or that Riquinho would show up. The Alloccos held their breath, waiting for the official, who eventually consulted his terminal, looked up, and handed back their passports. “You may go,” he said. Walking to the gate and boarding an actual plane felt like a dissociative dream.

It wasn’t until they were over the Atlantic that they started to relax. They’d awoken to a glorious sunrise, changed planes in Lisbon, and were now securely and irrevocably on their way home. The daze had not worn off. It was hard to believe any of this happened. It was even harder to think about what would come next.

An hour out from New Jersey, panic set in. Patrick Sr. was supposed to be saved by this gig; now he was further in debt. Patrick Jr. had been promised a cut of the proceeds, which he’d use to get back on his feet — a prospect long gone.

“Now where do I live?” Patrick Jr. said.

“I don’t know what to tell you,” Patrick Sr. said. “I don’t have a penny to my name.”

The conversation got heated. They were in middle seats, and the people on either side got uncomfortable as the Alloccos raised their voices. “What am I supposed to do?” Patrick Jr. yelled. “I can’t just go back to being homeless.” Patrick Sr. said his house was in foreclosure and that he wasn’t sure how to keep a roof over his own head. “This is fucked up,” Patrick Jr. said. “I’m going back to nothing.” He had no money, no job, no place to live. But he did have Rachel — and the promises he’d made to her.

Patrick Jr. knew Rachel was waiting for him at the airport. They’d reforged their connection, more honest and intimate than before. But her expectations were high. He’d never led a life anything like the one they’d talked about all those late nights in his room at the Epic Sana. For starters, he was only kind of sober. He didn’t even have a driver’s license. Descending over New York Harbor, his heart was racing.

Patrick Jr. didn’t know it yet, but he would indeed live up to his promises. It would take a while — there would be fits and starts and detours and relapses — but he would learn to fight for his sobriety, join the ironworkers union, knock rivets 300 feet above the East River, marry Rachel, buy a house, have three children. And Patrick Sr. would become a doting grandfather, digging himself out of debt by working at Starbucks, then landing a job with the New Jersey Lottery. (He also sued Nas for $10 million and ran for Congress. Neither effort succeeded.) Father and son would develop an even deeper friendship, still talking every day, even though they were no longer trapped in the same room.

With time, they would recognize that Angola brought them together when nothing else could. (In an unlikely commemoration of their captivity and reunion, Erickson would later reappear on Facebook and become friends with Patrick Jr. again. He sent the Alloccos their own Angolan flag for Christmas.) In a way, they realized, Nas did them a favor. In absentia, he turned out to be an unlikely but effective therapeutic facilitator. One who succeeded where all the rehabs and family counselors had failed. If they’d never gone to Angola, or if Nas had arrived as planned, Patrick Jr. says, “I would surely be dead.”

The plane touched the tarmac. Calm returned to the Alloccos. Whatever their fate would be, it was here. Unless, as Patrick Jr. joked before they got off the plane, “we are just going to wake up tomorrow and be back in that hotel room.”

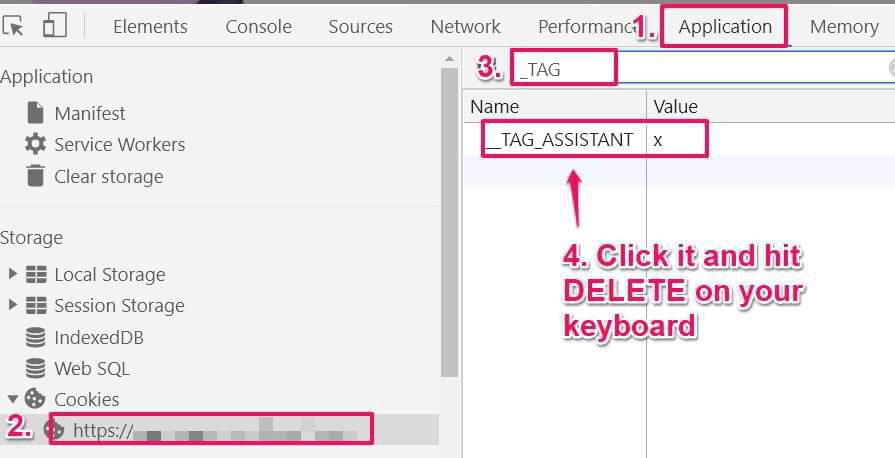

Illustration: Zohar Lazar

No one has ever been so happy to see Newark International Airport. When the Alloccos arrived at the gate, a police escort was waiting. Patrick Jr. was more accustomed to running from police, but now they were walking him through customs like VIPs. On the other side, the Alloccos were greeted with fanfare — family, press, and supporters like the deputy mayor, a local surgeon, and long-lost acquaintances, including a theater professor from college Patrick Sr. had not seen in 29 years. They’d be on TV that night, in the papers the next day. News cameras caught Patrick Jr. sweeping Rachel into his arms for a kiss, like a doughboy back from the Great War.

The welcoming party broke, and it was time for everyone to go their separate ways, which came almost as a surprise. But Patrick Sr. had to go home with Abby, and Rachel revealed that it was her brother’s birthday and she wanted to bring Patrick Jr. to the family dinner. “I guess I’ll see you later,” Patrick Jr. said to his father as they made for the doors of the terminal. And just like that, the two parted ways.

Rachel took Patrick Jr. to her apartment, where he unpacked, threw on some cologne, and tried to iron his rumpled clothes. After 49 days in Angola, it felt strange to walk into Dino & Harry’s Steakhouse in Hoboken, where Rachel’s family was waiting. He’d only casually met some of them, mostly as just some guy Rachel was seeing the previous summer. Now they were all sitting down together for a birthday celebration, ordering a rib-eye, choosing sides, passing the steak sauce.

He’d been on the ground for just a few hours. So far, Rachel and Patrick Jr. hadn’t talked much about their relationship plans, but it already felt natural to be back together. I guess we’re really doing this, Patrick Jr. thought.

“Everyone, this is Pat,” Rachel said for introductions. “He just got home.”