The warning this month from the United Nations was perhaps its starkest yet on climate change — society as a whole hasn’t done nearly enough to curb greenhouse gas emissions. But the alert also sounded a rare hopeful note: It’s not too late to stop the progression of Earth’s too rapidly rising temperature.

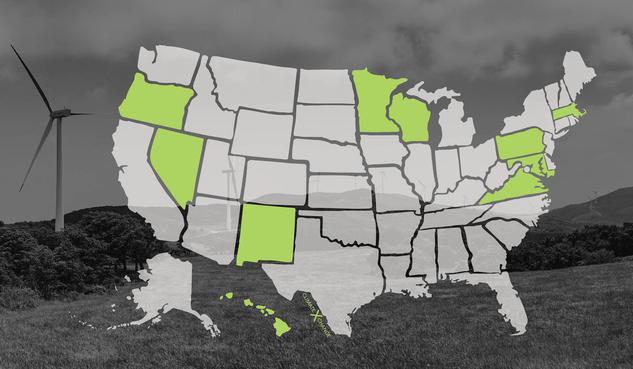

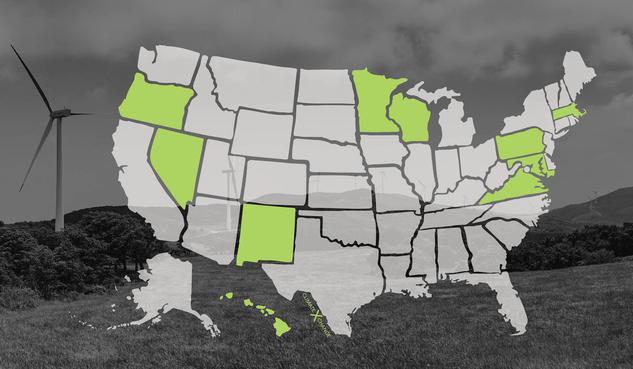

Oregon has heard the alarm and emerged as a cutting-edge leader among states poised to make a difference, advocates say.

Through legislation, a sweeping executive order by Gov. Kate Brown and environmental regulations, the state has ambitious plans to cut climate-warming emissions by 50% by 2035 and by 90%, possibly more, by 2050.

Yet even states like Oregon have much work remaining to avoid the catastrophic wildfires, drought and heat waves that have hit over the last several years.

“A few years ago we thought Oregon was going to be a refuge from climate impacts, and now it’s the poster child,” said Meredith Connolly, Oregon director of Climate Solutions, a nonprofit working to wean the world off of fossil fuels. “There is no one silver bullet policy to solve climate change, but we need to holistically accelerate the transition from fossil fuels to clean energy across all sectors.”

It’s also not clear if Oregon’s ambitious timeline will come to pass. Political fights, lawsuits and lack of consensus on how far to go and when are all part of a complicated equation that will play out over the next decade. Businesses, utilities and industry groups have challenged the authority of state agencies working to rein in carbon dioxide emissions, and the fate of some programs ultimately will depend on the outcome of ongoing court battles.

Oregon is doing better than most, said Nora Apter, climate program director at the Oregon Environmental Council, an advocacy group based in Portland.

“It’s important to acknowledge progress,” Apter said, while also noting that even Oregon’s goals fall short of what scientists say will be necessary to avert worsening climate impacts.

“We have set important targets, but they are still not in line with what the (United Nations) is saying,” she said. “This international body of scientists has long underscored this is the decisive decade for climate action. Fossil fuels are not needed anymore. We have the solutions at our fingertips to accelerate the transition to a clean energy future.”

‘BROKEN CLIMATE PROMISES’

The report published last Monday by the United Nations’ Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change focused on greenhouse gases — carbon dioxide, methane and other gases in the atmosphere that trap heat on the Earth’s surface.

The group of scientists from 195 member-countries who periodically assess the state of climate science for policymakers around the globe was blunt in its appraisal of efforts to curtail emissions: They have fallen woefully short.

United Nations Secretary-General Antonio Guterres said the report cataloged a “litany of broken climate promises” from countries that have pledged to cut emissions, then failed to live up to their word, putting humanity “firmly on track to an unlivable world.”

“This is not fiction or exaggeration,” Guterres said. “It is what science tells us will result from our current energy policies.”

But the report was not all doom-and-gloom. The world has the technology to drastically slash emissions and the cost to do so has fallen to a point where a rapid transition from fossil fuels to clean energy is feasible, the report concluded.

In 2015, member-countries of the panel met in Paris and committed to cutting greenhouse gas emissions to keep global temperatures from rising more than 2 degrees Celsius (3.6 Fahrenheit) above pre-industrial levels, with aims to keep them under 1.5 degrees (2.7 Fahrenheit), the threshold after which scientists agree expensive and deadly extreme weather events will become far more common.

Temperatures have already increased by 1.1 degrees Celsius since pre-industrial times, according to the report. Global emissions in 2019 were 12% higher than 2010 levels and more than 50% higher than they were in 1990.

The report’s authors wrote that, unless drastic cuts to emissions are made in short order, the Earth will warm by 2.4 to 3.5 degrees Celsius by the end of the century.

In the United States, about a third of all greenhouse gas emissions come from transportation, a quarter from electricity production and just over 20% from industrial sources. The rest comes from commercial and residential buildings as well as agriculture.

Deep cuts are needed across all sectors, the report said.

OREGON INITIATIVES

Over the last two years, Oregon has taken large steps toward meeting the commitments made in Paris.

In March of 2020, Brown signed Executive Order 20-04, which ordered state agencies to consider emissions reductions as a top priority in all their actions and to use their regulatory tools to seek carbon reductions in specific sectors to move the state toward its goals. The state is aiming to reduce emissions 45% below 1990 levels by 2035 and 80% below 1990 levels by 2050 through a series of new rules.

The mandate was bold, with only eight other states having similarly lofty goals and only one, New York, with a timeline as aggressive as Oregon’s.

Then last July, state lawmakers passed HB 2021, which requires the state’s two largest electric utilities to produce 100% clean electricity by 2040, meaning all power would need to come from renewable sources like wind, solar or hydropower. The bill also prohibits new or expanded natural gas-fired power plants in the state.

Soon after the executive order was signed, the Oregon Department of Environmental Quality began to look for ways to reduce greenhouse gases, eventually crafting what would come to be known as the Climate Protection Plan.

The plan, which went into effect earlier this year, puts a cap on emissions from fossil fuels across numerous sectors — including transportation, residential, commercial and industrial — that gradually lowers the amount of emissions allowed in Oregon. The plan requires a 50% reduction in emissions compared with today’s levels by 2035 and 90% by 2050, slightly higher than the goals outlined in the executive order.

Richard Whitman, the director of the Department of Environmental Quality, pointed to other initiatives, including incentives for biofuels and rebates on vehicles with low or no emissions, which are available to consumers now, as complementary pieces to the state’s strategy.

“Those things together paint a really promising picture,” he said. “We’re excited about that. While we are dealing with the climate crisis and the terrible impacts it’s having, we are seeing some significant gains.”

Connolly, of Climate Solutions, said these are important steps toward meeting the goals designed to reduce global warming.

“What we have to do as a state is get our electric grid to 100% clean energy, replace coal and gas plants with solar and wind and storage and our existing hydropower system,” she said. “With a carbon-free electric grid, we can then plug in as many systems as possible, electrify our cars, our trucks, our buses. Those are the biggest pieces of what we can do to replace fossil fuels in our state.”

Recent advances in wind energy, solar panels and gas-free appliances like electric heat pumps have made these kinds of big changes more practical than ever before, Connolly said.

“This transition from fossil fuels to clean energy is technologically feasible and affordable,” she said. “But entrenched interests are getting in the way.”

PROGRAMS FACE PUSHBACK

Many of the goals outlined in Brown’s executive order began as bills that died in the Legislature.

In 2019, Republican lawmakers walked out of the Legislature to deny Democrats the quorum necessary to vote on a bill that would have implemented a “cap-and-invest” strategy to cut greenhouse gases. A cap on emissions would gradually lower with companies required to buy or trade “allowances” among each other for each metric ton of carbon dioxide.

A similar bill in 2020 met with the same fate after Republicans again left the Capitol to prevent a vote on the measure.

Both bills faced stiff opposition from Republican lawmakers and business interests who said the initiatives were costly job killers and would disproportionately affect rural Oregonians.

Soon after the 2020 walkout, Brown signed her executive order on climate change.

At the time, the Partnership for Oregon Communities, a coalition of employers and farmers opposed to the governor’s action and previous versions of the climate legislation, put out a statement saying Brown’s “administration has unfortunately decided to move forward on a path that will put taxpayers on the hook for significant litigation costs, with outcomes that are far from certain.”

Last month, utilities, businesses and industry trade groups filed three separate suits against the Department of Environmental Quality to block implementation of the Climate Protection Plan.

The Oregon Farm Bureau, one of the groups suing, said the regulations would create a burden for oil and gas companies that would end up being passed on to consumers “and would impose significant new fuel costs on all Oregonians, which we know Oregon’s family farms and ranches cannot afford to pay.

“In enacting these rules, DEQ acted well outside its authority,” a statement from the Farm Bureau read. “Oregonians should not stand for a state agency creating policies that it does not have the authority to write, and it sets a dangerous precedent for the future.”

NW Natural, one of the utilities suing the state, also took issue with the state’s authority to enact the rules and said the program “lacks accountability, will be costly for customers and is unlikely to result in all the emission reductions customers will be paying for,” the utility wrote in a March letter to customers.

Whitman said the new rules are “entirely consistent” with the authority his agency has to regulate polluters.

“The broad authority to deal with air pollution was given to DEQ right from the get go by the Oregon Legislature and we’re using it today to address greenhouse gas emissions in the state,” he said. “Ultimately it will be up to a court to decide.”

For its part, NW Natural has touted its own voluntary pledge to reduce its emissions by 30% from 2015 levels by 2035 and its ramped-up use of “renewable natural gas,” which is typically methane harvested from landfills, livestock farms and food production facilities.

Behind carbon dioxide, methane is the second most prevalent greenhouse gas in the atmosphere, but is far more efficient at trapping heat. It accounts for about 10% of greenhouse gas emissions in the United States, according to the Environmental Protection Agency, but its impact on climate is roughly 25 times greater than that of carbon dioxide.

Though “renewable natural gas” may come from more environmentally friendly sources, Apter of the Oregon Environmental Council contends the utility is using the alternative fuel as cover to continue business as usual.

“NW Natural is advertising that they are cutting pollution by using renewable natural gas, but it’s still methane,” Apter said. “The IPCC says we have to cut methane by a third so it doesn’t make sense to use alternative fossil fuels. The solution is electricity and efficiency.”

NW Natural did not respond to a request for comment.

GAPS REMAIN

All of the moves Oregon has made over the last few years — the executive order, the clean electricity bill and the Climate Protection Plan — are encouraging signs of progress, Apter said, but she believes the state could do more to avert worsening impacts of warming.

“Nearly 40% of emissions in Oregon come from tailpipes,” Apter said. “That’s a critical piece of the puzzle. We need to rethink what our transportation system looks like. We have an opportunity to be more equitable, to be safer through investing in walkable, bikeable, transit-friendly neighborhoods, where people don’t have to use a car to get around for everything.”

In last year’s massive federal infrastructure funding bill, Oregon received roughly $1.2 billion, two-thirds committed to specific uses — bridge repair, earthquake resilience and electric vehicle infrastructure. The other third, more than $400 million, was essentially discretionary spending for the state’s transportation commission, which decided to spend the vast majority of the money fixing and maintaining highways and making safety upgrades on state roads.

Apter said that decision represents a huge missed opportunity. The money could have been better spent, she said, to expand bike lanes, bolster public transit or invest in an electric vehicle charging network.

“All state agencies have a mandate to prioritize climate and equity in their decision-making,” she said. “When choosing to focus on things like cars as the primary way to get around, they are not living up to their mandate. If they aren’t putting action to go with their words, it’s not going to get us where we need to be.”

Where Oregon, the nation and the world end up will depend on the priorities of those elected to make the decisions and the people chosen to carry them out, Connolly said.

“While the scale of the crisis is huge and the timeline for action is short, most of the solutions already exist and the economics are in our favor. What stands in our way is politics and status quo bias,” she said. “Overcoming those hurdles is the decisive work of our decade.”

– Kale Williams; kwilliams@oregonian.com; 503-294-4048; @sfkale

Note to readers: if you purchase something through one of our affiliate links we may earn a commission.