This is Geek Week, my newsletter about whatever nerdy things have happened to catch my eye over the past seven days. Here’s me, musing about something I don’t fully understand in an attempt to get my head around it. If you’d like to get this direct to your inbox, every single week, you can sign up here.

One of my favourite pastimes is reading charts on solar energy output.

That sounds perhaps underwhelming. But it’s just so much fun. The news is systematically a depressing place – “one plane crashed in China today” is a much better headline than “4.5 billion passengers took off and landed safely in 2019”: “a person was murdered in London today” is a better headline than “Nine million Londoners had a broadly uneventful day”.

You could say that that’s because we like bad news, and maybe that’s true, but you don’t need that to explain it: you can just as easily explain it by saying that events tend to be bad, while good news tends to happen in trends. A child dying is bad. Child mortality dropping by 90 per cent over the last 200 years is good, but there’s no single day you can put that on a banner headline.

Solar is very similar. If you look at a chart showing how much energy we create using solar, it goes up in an absolutely classic exponential curve. The trend is astonishing: the cost of a megawatt-hour of solar energy has gone down by about 15 per cent a year since 2010, if I’m reading the chart in this Bloomberg analysis correctly (which one of the authors reassures me that I am). Meanwhile, the number of megawatts installed goes up by something like 30 per cent a year. The total is still only about 1 per cent of global energy supply, but if the last two years have taught us anything, it’s that exponential curves go up quickly.

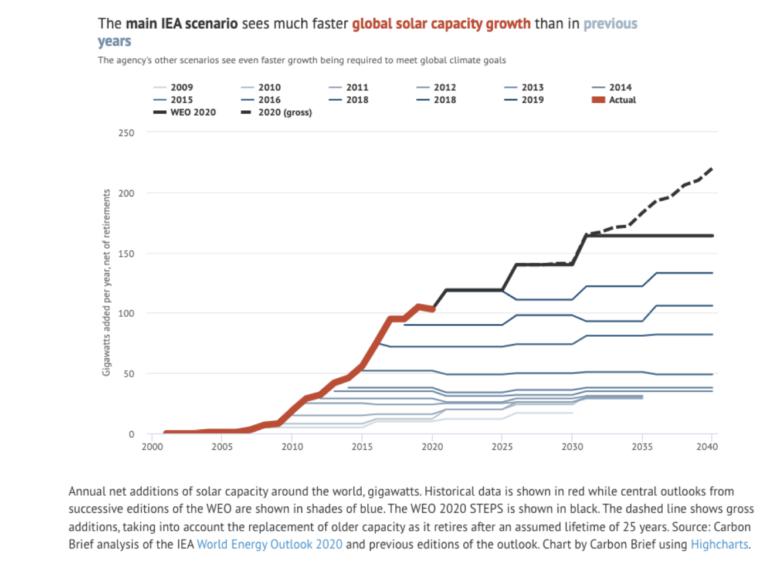

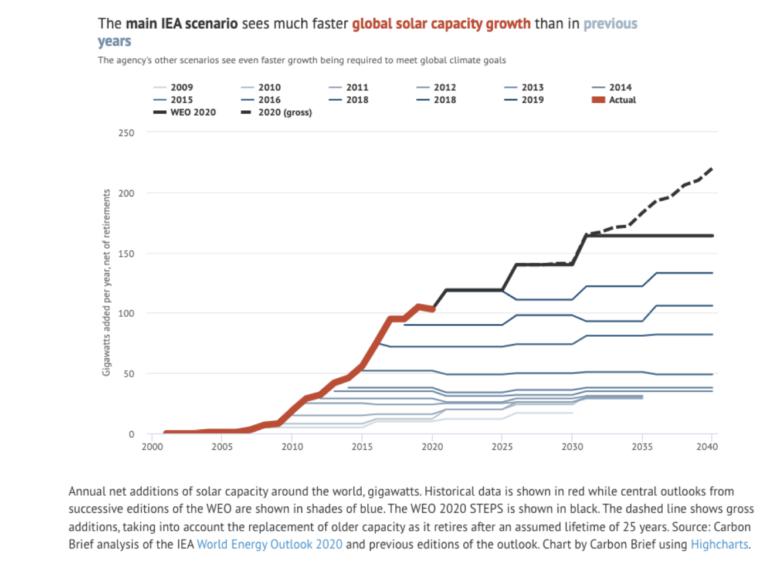

(Amusingly, the IPCC and International Energy Agency don’t see it that way: the IEA in particular repeatedly forecast that new solar would level off each year, and each year was wrong, and then did it again the next year: see chart below.)

And it’s not just solar. Last week I was introduced briefly to someone called Tony Seba, the co-founder of a think tank called RethinkX, and ended up reading some of his work. He points out that you see exponential curves like this in all sorts of new technologies: they take a little while to gather pace, and then they zoom up, and rapidly displace whatever they’re competing with.

From this RethinkX report, for instance: GMO corn was ≈10 per cent of US corn production in 1997. It’s ≈90 per cent now. Essentially 0 per cent of cameras were digital in 1994, now essentially 100 per cent. Physical media made up 95 per cent of video sales in 2005; it’s about 10 per cent now, replaced by digital downloads and streaming.

That report was pointing out that existing technologies – renewable energy production and storage, meat-replacement tech, electric and autonomous vehicles, that sort of thing – are all on exponential upward curves, and if you extend those curves upwards in the same way that they’re doing now, you get some pretty incredible results: upward of 90 per cent of all carbon emissions replaced by mid-century, that sort of thing.

The one that fascinates me in particular, although they all do, is the growth of electric vehicles. If you want to decarbonise the economy, you need to get everything running on electricity, as far as possible. At the moment, most cars run on fossil fuels, and transportation is a non-trivial chunk of our carbon emissions.

But the growth of electric vehicles is, once again, exponential. Sales in 2021 were twice what they were in 2020, and 2020 not far off double what they were in 2019. Before then, eyeballing the chart in the RethinkX report, they were probably going up about 40 per cent a year. It is, the report says, a virtuous cycle: increased demand leads to more supply, which lowers cost through economies of scale and increases public acceptance, which leads to more demand, which, etc. And in the meantime, the old technology – in this case, internal-combustion engines – lose demand, so they lose the economies of scale, and become less accepted, and so lose more demand. The report thinks that all new vehicles will be electric by the end of this decade.

I am instinctively optimistic, and love being told that the free market will solve all our climate problems without our having to destroy the economy and ruin everyone’s lives. So I need to be wary of things that tell me exactly what I want to hear. And there may be all sorts of reasons why simply extending the growth curve out naively is the wrong thing to do.

But for lots of other techs, it’s been exactly the right thing to do, and people haven’t done it, and are then surprised when smartphones go from niche to ubiquitous in five years.

The really exciting but somewhat more speculative aspect, though, is how the rise of electric vehicles interacts with developments in autonomous vehicles. Seba et al predict that the idea of owning a car at all will start to become outdated in the late 2020s: instead, we will have “transport as a service”, a fleet of autonomous electric vehicles which you can order when you need one, at huge savings to the consumer and vastly reduced demand for new cars, parking infrastructure, and, of course, oil. RethinkX’s transport-specific report is here, and it predicts that “By 2030, within 10 years of regulatory approval of autonomous vehicles (AVs), 95% of U.S. passenger miles travelled will be served by on-demand autonomous electric vehicles owned by fleets, not individuals.”

I really, really want that to be true. Cities that aren’t dominated by cars; a transport sector that doesn’t pump out carbon dioxide and particulates; and being able to sit and read a book instead of focusing on the damn road. And, of course, not having to own a car. Maybe it’s overly optimistic, but I love the sound of it.

The Spring Statement, despite rumours, did not announce a cut to electric vehicle subsidies. But it wouldn’t really have mattered if it did. Just as with solar, the cost is going down and the sales volume is going up: the economy is doing that on its own, and subsidies can speed it up, but it’ll happen anyway. Hopefully the autonomous vehicle bit works out too, and I can have a new favourite pastime, of watching the number of robot car journeys going up and the number of internal combustion engines on the roads going down.

Blogpost of the week: We’re going to have to solve climate change with capitalism

This week’s edition has been wish-fulfilment on my part, hoping that the workings of the capitalist economy will solve climate change without the need for major restrictions on Western lifestyles. So in keeping with that, I thought I’d share a post by the journalist James O’Malley, on why that is pretty much the only way that climate change can be solved.

He points out that for large parts of the left, you can only solve climate change via a societal revolution. Climate change isn’t a technological problem to be solved but a good-and-evil struggle for the soul of the planet, and to win it, we need to end capitalism and embrace a new, more equal vision of society.

But James says that we haven’t got time for that.

The scientific and worldwide political consensus is that 2050 is the point of no return. That’s only thirty years away. That’s not a very long time to do something, and it’s an even shorter time if before we can tackle climate change we have to remake capitalism, hang the billionaires and whatever else first.

I mean, Britain is struggling to build a single new railway line and change the planning rules to build a few more new houses. So building a worldwide, or even national political consensus around a much wider range of left-wing policy demands is a pretty tough ask.

The reality is that as far as the climate is concerned, we don’t have the luxury of time. We’re already at the scene in Apollo 13 where the NASA guy slaps down a bunch of junk on the table, and the people in the room have to figure out how to save the astronauts using only what is in front of them.

…the solution is going to probably lie in really boring stuff, like fiddling with taxes or the government underwriting loans in order to shift incentives towards low-carbon activities. It probably means that by 2050 we’ll still have lots of problems. The bankers will still be getting rich. There will still be income inequality. Power will still be unevenly distributed across society. But at least hopefully, the amount of warming will be limited.

I’m a boring technocrat with a severe distrust of underpants-gnome “Step 1: Revolution! Step 2: ??? Step 3: An end to the climate crisis!”-type solutions, so this ticks all my boxes. You could pair it, if you like, with Matt Yglesias’s argument that if everyone thought like economists, we’d solve climate change a lot faster, not least because governments could impose a carbon tax without being immediately thrown out of office by furious voters.

This is Geek Week, my newsletter about whatever nerdy things have happened to catch my eye over the past seven days. Here’s me, musing about something I don’t fully understand in an attempt to get my head around it. If you’d like to get this direct to your inbox, every single week, you can sign up here.